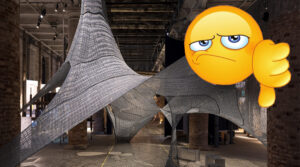

The Venice Architecture Biennale has historically served as a platform for the display of architectural innovation from across the globe. However, in recent years, particularly in its latest, it appears to have lost its focus on the true essence of architecture. What should have been a celebration of the discipline’s problem-solving creativity has increasingly devolved into a confusing showcase of poorly conceived artistic expressions masquerading as significant commentary.

Architecture is distinct from art. While it may draw inspiration from artistic fields, and can indeed be aesthetically pleasing or emotionally resonant, its core lies not in metaphor but in functionality. Architecture is fundamentally about addressing tangible issues within physical spaces, for actual individuals. Yet, the presented exhibitions at Biennale aren’t buildings, systems, or solutions, but ambiguous installations, and conceptual exhibits that seem more suited to an art biennale than the architecture one.

Rather than plans, elevations, and sections, we are presented with fabric drapes, films, and sculptural abstractions. Instead of concepts rooted in engineering, social infrastructure, or climate resilience, we encounter metaphor-laden discourses on identity, decolonization, or environmental issues. The issue is not with the exploration of these themes, it’s with the medium they are presented through. Architects who attempt to adopt the role of conceptual artists provide gestures in place of strategies, moods instead of mechanisms. In doing so, they aren’t doing the job of an architect.

This is not to suggest that architecture must always be literal or inflexible, but when architecture strives too earnestly to emulate art, it forsakes its primary purpose. The discipline does not require more vague metaphors; it demands a vision grounded in reality. Architecture should be straightforward. It ought to confront human needs and spatial challenges directly. A well-designed building speaks.

At the core of this issue lies a rising inclination to merge architecture, and design in a broader sense, with art. However, architecture is not art. Neither is design. The persistent assertion that they are is undermining the strength and intent of both.

Art is inherently subjective. It represents a personal expression of an artist, their thoughts, emotions, and identity. Its purpose is to provoke, to question, and to evoke feelings. It is not limited by functionality. A painting does not have to shield someone from rain. A sculpture does not need to ensure access to clean drinking water. Art exists for its own sake. It poses questions but rarely provides answers.

In contrast, architecture and design are objective fields with real impacts. They focus not on the creator but on the user. They are not mediums for self-expression but instruments for communal use. A building must endure. A chair must support weight. These characteristics are not optional, they are fundamental. If a building does not fulfill the requirements of its users, it is not a misunderstood masterpiece, it’s a failure.

Effective design and architecture are grounded in functionality. They aim to resolve issues, not to convey emotions. They cater to a diverse range of individuals, not merely a singular perspective. Certainly, beauty and creativity play a role in the process, but they are never the primary focus. A well-constructed bridge or a thoughtfully designed school may be aesthetically pleasing, even inspiring, but their value is determined by their functionality, not by their emotional impact.

The current trajectory of Biennale is particularly disheartening for this reason. Instead of showcasing buildings, infrastructure, or systems that address the pressing issues of our time, such as housing, climate change, and urban density, we are presented with abstract installations that aim for poetic expression but ultimately come across as empty. The work fails to resonate because architecture is not a medium for individual narratives. It is a collective endeavor. It must respond to the community, not to individual egos.

When architects attempt to play the role of artists, they frequently ignore the discipline and accountability that architecture needs. In doing so, they not only bewilder the audience but also undermine the integrity of the field.

History is filled with brilliant discoveries and revolutionary technologies that never had the chance to reach their full potential. Sometimes, it’s not because the idea didn’t work, but because it threatened powerful financial interests.

History is filled with brilliant discoveries and revolutionary technologies that never had the chance to reach their full potential. Sometimes, it’s not because the idea didn’t work, but because it threatened powerful financial interests.

Although democracy and innovation aren’t a perfect symbiotic pair, their relationship is deeply intertwined and they greatly depend on each other.

Although democracy and innovation aren’t a perfect symbiotic pair, their relationship is deeply intertwined and they greatly depend on each other. In today’s world, the line between artistic expression and commercial interest is blurring faster than ever, raising important questions about what art truly means in a consumer-driven culture.

In today’s world, the line between artistic expression and commercial interest is blurring faster than ever, raising important questions about what art truly means in a consumer-driven culture.